Why do Limbus oppose the Pathibhara cable car?

On the ongoing protests against the planned cable car in eastern Nepal

Good morning, good afternoon, and good evening from Kathmandu. This is Issue 168 of KALAM Weekly, the only newsletter you need to keep updated with everything happening in Nepal. This week, we have a very necessary guest post from Sandesh Ghimire, a writer and filmmaker. He writes about ongoing protests in eastern Nepal, Taplejung, against a planned cable car. More in the deep dive below.

Before we begin, thank you to my newest paid subscribers, Elina Pradhan and Logan Emlet, for your support and trust. I greatly appreciate the love you paid supporters have shown me over the years. I am very grateful. If you would like to subscribe, please click the button below or scroll down for more information!

In this newsletter:

An update on the Kantipur article about Sujeeta Shahi

Can Nepal’s buff export to China be a game changer?

Political interests once again take precedence over Tribhuvan University dean appointments

What is happening with Rabi Lamichhane?

Recommendations

The Deep Dive: What is happening with the planned cable car in Taplejung?

An update on the Kantipur article about Sujeeta Shahi

Last week, I wrote about the strange case of Sujeeta Shahi, a supposed “war journalist” turned skydiver. The day the newsletter was published, Kantipur issued a lengthy clarification on the article, which I unfortunately missed. That is on me and I apologize for the oversight. The newsletter should have taken the clarification into account. So in the interest of transparency, I’m going to address the clarification here.

The clarification, issued by the editor-in-chief, has five points. All other points, except for the third, are irrelevant since they clarify questions no one asked. The third point addresses the bulk of the criticism against Shahi, which pertains primarily to her alleged past as a “war reporter” and a special forces commando in the German and, later, Austrian Army. Kantipur says Shahi was unwilling to share any supporting evidence of her journalism or military experience. “You will not find any evidence of an undercover job on Google, nor can I share any details with you,” she reportedly told Kantipur when they asked for evidence. Regardless of her statements, since her claims could not be verified, they should not have been included in the feature article, Kantipur concludes.

The final point is funny in just how defensive it is:

Almost everyone who came into contact with Kantipur openly praised Sujeeta Shahi as a professional, independent and courageous person. However, in our attempt to present a story that gives a positive message to a society gripped by despair, we acknowledge that some naturally arising questions were not addressed and we express our commitment to further strengthen our fact-checking system.

Despite this lengthy clarification, the story remains online with no edits. Nowhere in the article does the editor-in-chief or the reporter apologize for publishing a story with blatant oversights in fact-checking and corroboration. Instead, the chief editor excuses the story by saying that they were attempting to “present a story that gives a positive message to a society gripped by despair.” That’s a very weak justification, and it justifies nothing. At least previous Kantipur editors, when they made mistakes, were willing to own up to them and either resign or apologize. Kantipur’s current editor, Umesh Chauhan, seems to believe that he doesn’t owe anyone an apology. That’s just sad and frankly, a little pathetic. At least journalism students will have lots of fodder on how not to do journalism and how not to issue a clarification.

Dear readers, thank you so much for reading and supporting this newsletter. We had set a new goal of reaching 120 paid supporters by the end of the year and we are almost there. We are currently at 115 supporters and if just another five of you pledge your support, we will be at 120! So please, if you are able, pledge a paid subscription. We are offering a 20% discount on all annual subscriptions. Readers abroad can click here to access the discount while readers in Nepal can click this link for more information on how to become paid supporters.

Your support allows us to keep this newsletter going, invest in more reporting, and pay our reporters fairly. All of the support you show us will go right back into making the newsletter better! Your support means the world to us!

Can Nepal’s buff export to China be a game changer?

Earlier this month, during Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli’s visit to China, the two sides signed a Memorandum of Understanding on the export of thermally processed buffalo meat from Nepal to China. Following up on that MoU, on Monday, another MoU of “Strategic cooperation for Nepal thermally processed buffalo meat products export project to China” was signed between the Nepali export company Himalayan Food International and the Chinese import company Shanghai Ziyan Foods. As part of the agreement, the Chinese company will invest $200 million in Nepal to develop a value chain for the export of buffalo meat, including “breeding, slaughtering, processing, logistics and trade.” The agreement, once implemented, is expected to result in approximately $1.5 billion in revenue for Nepal, while increasing average annual incomes by $7000 for over 200,000 households and generating 10,000 direct jobs and 1 million indirect jobs.

Sounds pretty lofty, doesn’t it? Already, Nepalis are hailing the agreement as a “game changer” for Nepal, but how feasible is a $1.5 billion export to China?

In 2022, Nepal’s total exports were just $1.43 billion, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity. This means that once fully realized, buffalo meat exports could double Nepal’s exports by itself. The operative phrase here is “once fully realized” as there is a lot Nepal needs to do before it can even get close to that massive figure. In the fiscal year 2021-22, Nepal exported 231.09 metric tons of buffalo meat, worth just about $323,703, a piddling number compared to the super-ambitious $1.5 billion target. So it baffles me how we will get to a billion dollars in exports from just a few hundred thousand.

This conundrum is further compounded by the fact that the General Administration for Customs of China (GACC) has strict regulations for the import of food products. Nepal does not currently meet any of those regulations and will need to overhaul the current slaughter and processing system if it hopes to export to China. That is perhaps what the $200 million investment from Shanghai Ziyan will go towards. But all that investment needs to be supported by policy and implementation. Nepal has a Slaughterhouse and Meat Examination Act in place, but a cursory walk to any neighborhood butchery should make it clear that this Act is very rarely enforced anywhere in the country.

So, optimistically, an extra $1.5 billion in exports would certainly be a game-changer. Realistically, it will likely take decades for even a fraction of that billion and a half to materialize, if it ever does.

Political interests once again take precedence over Tribhuvan University dean appointments

On Sunday, the Tribhuvan University executive council appointed eight deans to various research centers and faculties at the university. The Institute of Medicine, Institute of Engineering, Institute of Forestry, Institute of Agriculture and Animal Sciences, Institute of Science and Technology, Faculty of Management, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, and Faculty of Education all received deans after remaining vacant for six months. Unfortunately, there is criticism that almost all the deans were appointed based on their relationships with political parties rather than merit or seniority.

Political interests have long been part and parcel of Tribhuvan University, the country’s oldest and largest university. The parties use dean appointments to hand out positions to party loyalists, and the appointees, too, see it as a reward for their decades of lobbying for partisan interests. Student unions, too, affiliated with one party or the other, tend to carry out lobbying, which often turns violent in favor of their party’s choice for dean. It also doesn’t help that the prime minister is the ex-officio chancellor of all of the country’s universities and thus has final say over who gets appointed.

This political interference is exactly when Sumana Shrestha attempted to put an end to while she was Education Minister. Pushpa Kamal Dahal, who was prime minister at the time, had even pledged to end all political influence in schools and universities. He didn’t follow through, and now, all the major political parties — UML, Congress and Maoists — have asked for their pound of flesh. In Nepali, it’s called ‘bhagbanda’ or share and share alike. Instead of putting the futures of young Nepali students first, the parties have shown that they will continue to share everything just among themselves, everyone else be damned.

What is happening with Rabi Lamichhane?

Rabi Lamichhane, former Home Minister, former Deputy Prime Minister, and chief of the Rastriya Swatantra Party, has been languishing in police custody since mid-October. On Monday, December 16, the Kaski District Police filed a chargesheet against Lamichhane and 50 others for embezzling funds from banking cooperatives. The police have recommended that the district attorney charge Lamichhane and the others with fraud, organized crime, and money laundering. The district attorney will likely file formal charges in court today, December 20. If convicted, Lamichhane faces years in prison and hefty fines, in addition to an end to his political career, as criminals are not allowed to hold public office.

Whatever his crimes, the ruling government of the UML and Nepali Congress seem out to make a spectacle of him. Earlier this week, Kaski police leaked a photo of Lamichhane sleeping in his jail cell, a violation of his right to privacy. He has been transported from jail cell to jail cell, often in the middle of the night, to be presented before judges. He has been in judicial custody for two months now on the argument that he could destroy evidence if set free. But neither Lamichhane nor his party is in government. He has no avenue to destroy evidence, especially with the entire country watching. And yet, his judicial custody has been extended time and again, the last time being earlier this week. But custody cannot be extended any longer, as the law allows for a maximum of 60 days concerning organized crime charges, so formal charges need to be filed by December 20 at the latest.

The government might have killed the Rastriya Swatantra Party’s momentum with Lamichhane’s arrest and even destroyed the party’s chances at the next election, but not all has gone according to plan. Lamichhane is still welcomed by hordes of supporters wherever he goes. His party remains firmly behind him, and public sympathy is rising, given the administration’s antics of moving him repeatedly and without warning and leaking his photo from jail. Even those who weren’t on Lamichhane’s side initially are now saying that the government is going too far in its bid to punish him. The entire saga is looking more and more like a vendetta, aided and abetted by Kantipur daily, and realized by the mainstream political parties to whom he posed a threat.

Recommendations

Article: Nepal created a forest fund to do everything; five years on it’s done nothing, Abhaya Raj Joshi, Mongabay

Podcast: How Stockholm stuck, Radiolab

Music: I am Kurdish - Mohammad Syfkhan

That’s all for this week’s round-up. The Deep Dive continues after the break below.

The deep dive: Why do Limbus oppose the Pathibhara cable car?

Limbu activists demonstrate against the planned cable car in Taplejung. (Image: Sara Tunich Koinch)

by SANDESH GHIMIRE

Slightly over a month ago, on November 8, Arjun Prangden Limbu, a porter, was passing by a protest led largely by Limbus against the planned construction of a cable car in the eastern district of Taplejung. The protestors and the Armed Police Force were in a stand-off when “hired goons” infiltrated the protest and began to attack the protestors with khukuris and other weapons, Shree Linkhim, coordinator of the protest and an eyewitness, told me. Limbu was caught up in the clash and in the ensuing melee, nearly had his arm lopped with a khukuri.

According to researcher Sabin Ninglekhu, who posted about the incident on his social media, the attack was instigated by local goons hired by Chandra Prasad Dhakal, the wealthy CEO of the IME group conglomerate which is building the cable car. Shree Linkim, coordinator of the Mukkumlung Protection Struggle Committee, said that the police did nothing when the goons attacked the porter. The grievous injuries to the porter only exacerbated the protest, resulting in multiple injuries on both sides.

I met Shree Linkim and Saroj Limbu, also a member of the Mukkumlung “struggle committee,” recently at the Nepal Art Council, where they gave a talk titled “Mukkumlung ko prakriti, punji ra pratirodh” (The nature, capital and resistance of Mukkumlung). The talk, which touched upon various facets of the ongoing protest against the cable car in Taplejung, was part of the “Who does the river belong to?” exhibition. On display from December 13-22, the exhibition brought together photographers, artists, and activists to generate discourse about the environmental, cultural, and social costs of large-scale “development” projects like the cable car.

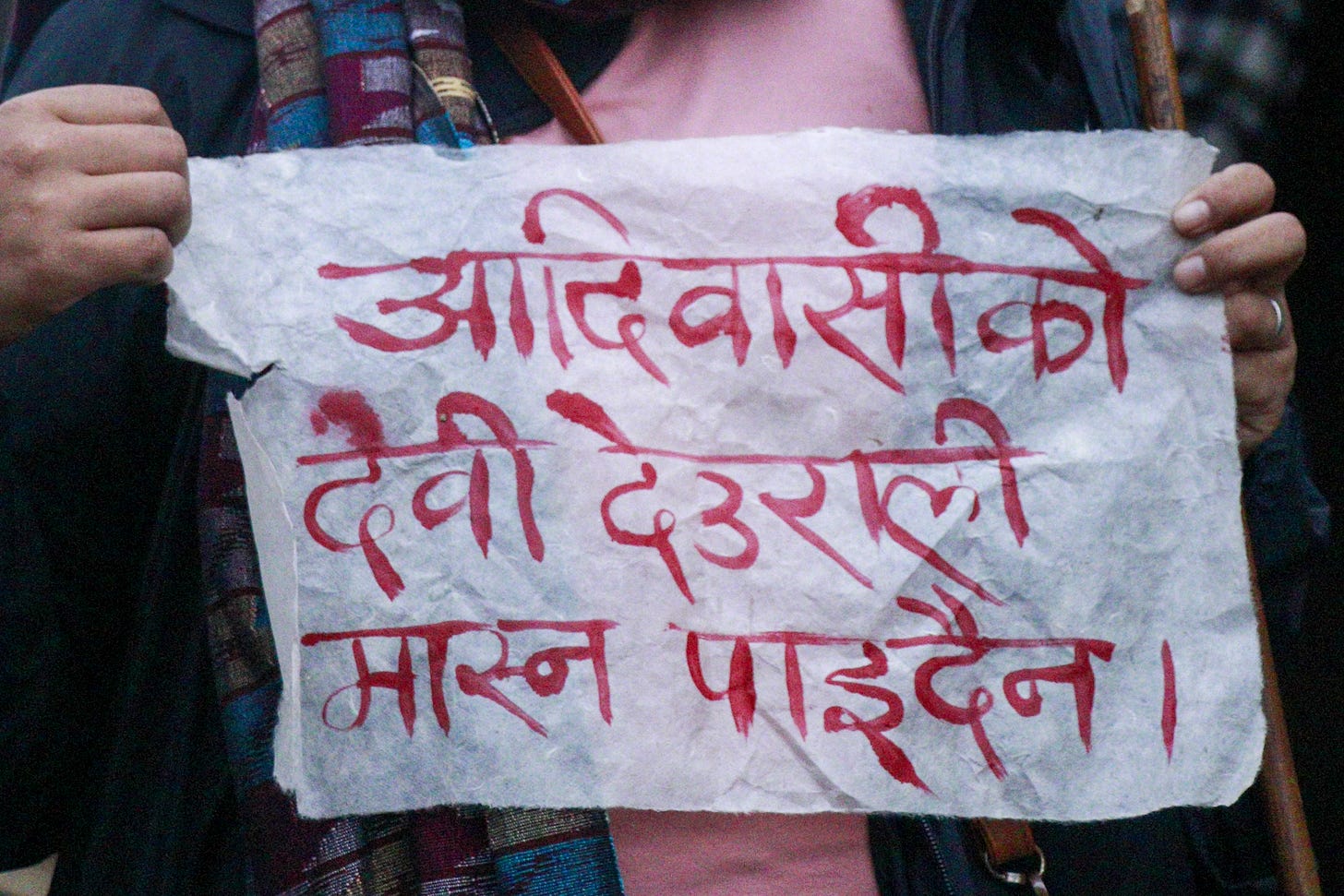

You cannot destroy the gods and hills of the indigenous. (Image: Sara Tunich Koinch)

The Pathibhara cable car project has emerged as a flashpoint in the long-standing push-and-pull between “development” advocates and local indigenous groups. The former claim that the cable car will increase tourism, create jobs, and bring economic prosperity to the region, while the latter argue that the cable car will desecrate the environment, destroy the sanctity of a sacred hill, and that any economic benefits will largely be limited to private investors. While there have been protests during the construction of other cable car projects in the country, this one exemplifies the many political, developmental, and ideological challenges that Nepal has historically struggled with.

For this explainer, I spoke to members of the struggle committee and consulted the work of researcher Kailash Rai. I also spoke with journalists Rabin Giri, Basanta Basnet, Marty Logan, and Tanka Dhakal, who helped me understand the situation in Mukkumlung. Their positions, however, might differ from my own.

Let’s start at the peak of the Mukkumlung hill in Taplejung. Mukkumlung is known in Nepali as Pathibhara, one of the holiest shrines for Nepali Hindus. But long before the Pathibhara temple was constructed, there used to be a large rock on the hilltop, worshipped by the Limbu people for its divine power. Limbus follow the Mundhum, an ancient religious and folk scripture that is animistic and shamanistic, very different from the majority Hindu religion. For the Limbus, or Yakthung as they call themselves, the rock, as well as the entire Mukkumlum hill, is the natural representation of the goddess Yuma Sammang. For Hindus, the rock was a symbol of the goddess Durga.

Things began to change in 1995 when the Pathibhara Area Development Committee was formed. Under the committee's direction, the divine rock was replaced by the statue of Goddess Durga in 2001. For the Limbus, this was yet another attempt by the Hindu state to wipe out their Indigenous culture. A space and a deity long revered by the Limbus were Hinduized and Sanskritized into Pathibhara. There is no mention of Pathibhara in any of the Hindu scriptures.

“Mukkumlung is the head from which all Limbu tradition flows. If the head is severed, Limbu culture will not survive,” Saroj Limbu told me.

The Limbu see this Hinduization as another betrayal in a long list of betrayals from the Hindu state, which began in 1774. Prithvi Narayan Shah, progenitor of the Hindu Nepali state, could not militarily overpower the Limbus. After numerous stalemates, a treaty was signed between the Limbus and the Gorkha king. Limbuwan would accept the suzerainty of Nepal in return for autonomy and legal recognition for their communal system of land ownership, known as Kipat in Nepali. But the state did not live up to its end of the bargain, encroaching on Limbu land and attempting to replace Limbu culture with a standardized ‘Hindu’ identity.

However, Limbus themselves are divided over the cable car. Dambar Dhoj Tumbahangphe, an influential local politician, and Amir Maden, mayor of Phungling Municipality, are both Limbus and have endorsed the project. Most of the loggers who came to fell the trees and the hired goons who assaulted Arjun Prangden Limbu were also Limbus. This divide is emblematic of the twin discourses that continue to animate Nepal’s development trajectory. While some believe that any price is worth paying for development, others believe that intangible heritage like religion and culture are worth protecting, even at the cost of development.

Even if we put aside the sociocultural concerns of the Limbus, there are many reasons – environmental and political – for why the cable car is problematic.

In 2018, the National Planning Commission declared the Pathibhara Cable Car a “national pride project,” meaning it would receive priority funding and policy assistance. The intended cable car will start near Kaflepati, at around 2,200 meters, and end at Mukkumlung peak, where the Pathibhara temple is situated at 3,794 meters. The tender for constructing the cable car was given to Chandra Dhakal’s IME Group, which operates a similar cable car in Chandragiri. IME Group was awarded the tender on the basis of a proposal to the government.

IME Group began work on the cable car earlier this year. In May, loggers under the protection of the Armed Police Force felled around 1,200 trees using heavy machinery. When local activists overcame the police roadblocks and stopped the loggers, Shree Linkhim said that 30 percent of the forest cover in Mukkumlung had already been cleared. In December 2018, the Cabinet allowed the logging of 10,231 trees, but activists claim that nearly 60,000 trees will be felled by the time the project is complete.

A symbolic protest against the cable car. (Image: Sara Tunich Koinch)

Felling thousands of trees is certain to have dire ecological consequences. In 2017, the government declared Taplejung as a protected sites for rhododendrons, Nepal’s national flower. Mukkumlung is also home to the engendered red panda. Both of these environmental concerns should have been included in the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) and influenced the work of IME Group, but the Nepal government has held the EIA report in close confidence. Shree Linkhim says that neither activists nor researchers have been able to access the EIA report. Lawyer Sanjay Adhikari and his team at Prakash Mani Academy for Public Interest Law have also made numerous attempts to access the EIA report as well as the Detailed Project Report (DPR), but they’ve been rebuffed each time.

There’s also the contention that Taplejung and the Mukkumlung area are prone to extreme weather events. People in Taplejung regularly die after being struck by lightning. Sara Tunich Koinch, a freelance photographer who exhibited her story about the Mukkumlung protests at the Nepal Art Council this past week, says that electrification efforts on the Mukkumlung hill too have failed due to frequent lightning strikes. IME Group must be aware of the environmental challenges of constructing a cable car in a place where extreme weather events are the norm. Despite these environmental concerns, the project has been endorsed by all of the major political parties.

So, why is Chandra Dhakal so keen on developing the cable car? He regularly tells the media that the cable car will bring “development” and “prosperity” to the area but if past experience is anything to go by, the only people getting rich will be investors like Dhakal. The Chandragiri cable car has been very lucrative for Dhakal as he holds a near-monopoly on all rest and relaxation offerings there. Saroj Limbu, a member of the Mukkumlung Struggle Committee, says that the government has granted Dhakal’s company a lease encompassing five hectares of land at Mukkumlung peak. Nearly 300,000 pilgrims visit Pathibhara temple every year, and a cable car will only increase this number. Any hotel, restaurant, or amenities built at the site will turn a tidy profit.

Furthermore, Dhakal’s modus operandi for large-scale infrastructure projects like these has been to list the project on the stock exchange and raise money from the public. The public will bear any losses, while Dhakal will profit from all the surrounding infrastructure that he will construct to support tourism in Pathibhara.

In addition to Pathibhara, Dhakal holds the license to build the Sikles-Annapurna Cable Car, which is located inside the Annapurna Conservation Area Project, another environmentally critical area. In January 2023, the Supreme Court gave an interim order to stop constructing the Sikles cable car due to environmental concerns. Lawyer Shankar Limbu has filed a similar case against the Pathibhara cable car at the Supreme Court, but the case has yet to be heard.

I remember the day when, as a six-year-old boy, my mother took my grandmother and me to Manakamana Temple. This was the first time my grandmother had left her village in Morang, eastern Nepal. As the cable car gondola swept us toward the temple, my mother declared, “This is heaven on earth. Look, Ama, look how we go up.”

Manakamana was Nepal’s first cable car, capturing the imagination of a whole generation of Nepalis. Riding the gondola up to the temple became a rite of passage. During the monarchy, environmental concerns and the aspirations of indigenous communities who lived on the hills where the cable car was constructed were easily cast aside in the name of development. But there is a newfound ethnic consciousness now, and we are more aware of the threat of environmental collapse. Any infrastructure that comes at the cost of a community’s ideals and the habitats of endangered species needs to be reconsidered.

The corporate aggression in Mukkumlung will be repeated in other parts of Nepal. Communities will protest. The question is, who will stand with them?

That’s all for this week. I will be back next Friday, in your emails, for the next edition of KALAM Weekly.

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, please consider sharing it with others who might enjoy weekly updates from Nepal or consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading KALAM Weekly! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Thank you for covering this and shedding some light. I've been following, reading and imbibing a lot of prose, poetry and stories from Indigenous storytellers and am always fascinated by their wisdom. From what I understand, Mundhum is of course an ancient + ancestral Yakthung legacy, but what impresses me most about it is that it is a sacred oral recitation passed down from one generation to another! Writing / documentation has been considered to be more of a western colonial concept and documenting stories through chronicling them into archives was normalized much later. And so, most Indigenous Peoples have relied on traditionally passing down the stories as oral historians. I think this is an important observation that also distinguishes the colonizer vs the colonized - Pathibhara cable car is another classic case. Whether it be North America's oil & gas pipe line or the Land-back movement or the Asian sub-continent's battle to stick to their Indigeneity, the idea of eternal return as popularized by Nietzsche prevails!

What is happening at Pathibhara? Parallels with Modi's destructive 'vikas' in the Himalaya

https://www.youtube.com/live/saU4MttbLcI