Good morning, good afternoon, and good evening from Kathmandu. This is Issue 160 of KALAM Weekly, the only newsletter you need to keep updated with everything happening in Nepal. I am back from Dashain break and have a brand new newsletter for you!

In this newsletter:

No relief yet for flood victims

KP Oli and Bhat-bhateni’s Min Gurung

Pashupati Area Development Trust vs Marwadi Sewa Samiti

Nepali peacekeepers in Lebanon

Rabi Lamichhane arrested

The Deep Dive: Reflections on Dashain and death

No relief yet for flood victims

It’s been three weeks since floods and landslides triggered by heavy rains devastated Nepal. Hundreds of lives were lost, and thousands were displaced. This latter group continues to live in makeshift shelters and the homes of friends and relatives, awaiting some relief from the government. And yet, three weeks on, they’ve not received any of the relief promised by Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli. The government pledged Rs 200,000 to each bereaved family, and while some of this money has been doled out, many more families await assistance. With the temperature dropping, there is a fear that they will have to spend the winter in makeshift shelters. This isn’t an unfounded fear, as after the 2015 earthquakes, hundreds of families spent years in temporary shelters. Two years ago, another earthquake struck Nepal’s Far West, and again, victims spent many hard winter months under tarpaulin and corrugated iron.

It’s not as if the government doesn’t have money. Aid has poured in, and the government has billions of rupees in disaster relief funds. According to Kantipur, the Prime Minister’s Disaster Relief Fund has accumulated Rs 1.74 billion in aid and donations from various sources. The disaster management fund under the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority has about Rs 1.6 billion. Besides these, every level of government—local, district, and provincial— has its own disaster relief funds. Still, bureaucracy and red tape have held up any relief to those who need it most.

Two weeks ago, the National Human Rights Commission had already urged the government to begin handing out relief. Needs are highest in the immediate aftermath of any disaster, and any relief helps. Nepal’s policies dictate that affected families are eligible for immediate relief of Rs 15,000 to Rs 20,000. This can go towards immediate food, sanitation and health costs as families displaced from their homes often have nothing at hand. However, all levels of government appear to be too busy collecting information and discerning who the actual victims are. This has always been the issue with disaster relief. The government is so paranoid that the unscrupulous will take advantage that it leaves all victims out in the cold, quite literally. Victims need relief, and the government needs to swing into action immediately before the winter sets in.

KP Oli and Bhat-bhateni’s Min Gurung

Why does a businessman accused of corruption “donate” nearly 11 ropanis of land (half a hectare) to house a political party’s headquarters? Why does he go even further and pledge to build the headquarters himself, at no cost to the political party? These are rhetorical questions. The answer should be obvious to anyone. Businessmen do not donate land and buildings to political parties. If they wish to indulge in philanthropy, they build hospitals, schools, libraries, and research centers, at least in other parts of the world. In Nepal, donating land and buildings worth billions of rupees to a political party, which in itself has billions in assets, is considered charity.

Min Bahadur Gurung, the owner of Bhat-bhateni Supermarkets, recently donated land and has reportedly promised to build the new headquarters of the CPN-UML party. The old headquarters was damaged during the recent floods in Kathmandu. The UML is the very party that Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli leads. On October 11, Oli gleefully laid the foundation stone for the new building and invited much criticism from the media and inside his own party. Binda Pandey, a UML party member and former minister, criticized Oli’s acceptance of the “donation” on social media, saying, “Those party members who had donated a day of their labor to the construction of the UML’s old party building 25 years ago still take pride in their contribution whenever they visit the GEFONT [General Federation of Nepalese Trade Unions] office. Are we now in a place where a party with 550,000 members, the largest party based on votes, takes pride in accepting donations to build a party office?”

Other party members haven’t been so publicly vocal but have expressed their reservations privately, saying they weren’t consulted and that it didn’t look good for a party to accept such a donation from a man accused of misappropriating public property. Some analysts say there would be no issue with accepting such contributions from a “national capitalist, someone who earned their wealth legitimately,” but I disagree. Gurung has been implicated in numerous scandals and was even handed a two-year jail sentence for his involvement in the Baluwatar land grab. Gurung, however, has not been jailed and is appealing the decision. But that aside, no political party should accept such large donations from any business interests. Such contributions always come with strings attached. Now, Oli might be willing to indulge Min Gurung and his Bhat-bhateni empire but evidently, not everyone in his party is on board with kowtowing to business interests.

Nepal’s political parties appear to have no qualms about accepting money from anyone. Earlier in October, right after the devastating floods, the International Department of the Chinese Communist Party handed over Rs 19.7 million to Nepali political parties, including the Congress, UML, and Maoists, as relief for those affected by the disasters. That contribution, too, was heavily criticized for not being channeled through the state. But then, too, the parties accepted the donation wholeheartedly. Reminds me of a certain character from the HBO show The Wire.

Pashupati Area Development Trust vs Marwadi Sewa Samiti

A row has erupted between the Pashupati Area Development Trust (PADT) and the Marwadi Sewa Samiti over the ownership of the Dharmashala. If those are too many proper nouns for you, let me break it down. The PADT is a semi-governmental body that oversees all activities within the UNESCO World Heritage Site, that is the Pashupati temple and its surroundings. The Marwadi Sewa Samiti (MSS) is a non-profit charity organization operated by the Marwadi community, which includes very powerful and wealthy businesspeople. The Dharmashala is a rest house for pilgrims to Pashupati, managed by the MSS since 2003.

So what’s the row? In 2003, the PADT and MSS signed an agreement for the latter to operate the Dharmashala for an annual rent of Rs 51,000. However, a few years ago, the PADT asked the MSS to pay more in rent, which was a reasonable demand given that Rs 51,000 is a pittance in annual rent, especially for a property being used for commercial purposes. The MSS refused, saying it was operating the Dharmashala as a charity and not making any profit. The PADT, however, argued that the MSS was operating for-profit hotels and restaurants and making over Rs6 million a year. Subsequently, PADT annulled its agreement with the MSS last year, which led the MSS to file suit against the PADT at the Kathmandu District Court. The MSS argued that it had been managing the Dharmashala long before the PADT even came into existence and that it had tenancy rights. The court threw out the case, saying the MSS had no ground, and then, earlier in October, the PADT decided to hand over the Dharmashala to the Kathmandu Metropolitan City.

That’s when things took a turn. Kathmandu Metropolitan City attempted to take possession of the Dharmashala, only to meet fierce opposition from the Marwadi community. Multiple attempts were similarly rebuffed, leading the city to ask for assistance from the District Administration Office. As fears of a violent clash grew, the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Civil Aviation stepped in and asked the PADT to halt all attempts at repossessing the Dharmashala. A meeting has been scheduled for Sunday to find an amicable way forward.

In a way both the MSS and the PADT are right. The MSS has been operating the Dharmashala for decades, providing much-needed rest and relaxation services for pilgrims. However, the PADT is also right to demand a higher rent, as Rs 51,000 is way too low for a commercial enterprise on the scale of the Dharmashala. The MSS, no matter how influential, cannot continue to insist that it will only pay this meager sum, especially when things have changed drastically since the agreement was first signed. Instead of annuling the entire agreement, perhaps the MSS and PADT could reach an agreemtnt to pay higher rent in return for continuing to operate the Dharmashala. After all, it seems that money is the biggest issue here. We’ll wait and see what Sunday’s meeting decides.

Nepali peacekeepers in Lebanon

On October 1, Israel, as part of its escalating war against all opponents in the Middle East, mounted a ground offensive into Lebanon to take down Hezbollah. The invasion has been heavily criticized by a majority of the world’s countries, except, of course, Israel and the United States. Israel has been acting even more belligerent, firing on UN peacekeepers in Lebanon and injuring a few.

UNIFIL, the UN Interim Force in Lebanon, was created in 1978 after Israel invaded Lebanon in response to the massacre of Israeli civilians by members of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, which was based in south Lebanon. UNIFIL’s mandate was expanded when Israel once again invaded Lebanon in 1982, when Israel finally withdrew in 2000, and again after the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah. As of September 2024, there were over 10,000 UN peacekeepers in Lebanon with a mandate to prevent armed insurgents like Hezbollah from taking over south Lebanon, carry out humanitarian work, and assist displaced peoples. Of these 10,000 plus soldiers, 876 are Nepali.

Israel considers UNIFIL, at best, incompetent and, at worst, actively aiding Hezbollah. In a way, it is right, as UNIFIL has largely failed in its mandate to prevent Hezbollah from rearming itself in south Lebanon. However, Israel knows very well how complicated the region is, and no outside force can impose its will on the Middle East. It has thus continued to target UNIFIL compounds and command posts. From 1978 to 2024, 326 peacekeepers had already been killed in conflicts between Hezbollah and the Israeli forces. Of these, 31 were Nepali.

Now, as hostilities exacerbate and Israel shows little regard for UNIFIL, there is a danger that more peacekeepers will die. It is unclear how many Nepali peacekeepers are currently in Lebanon and it behooves the government to clarify that number. Nepal has not yet issued any statements on the Israeli invasion or Israel’s deliberate targeting of UN peacekeepers. All it has done is sign on to a joint statement by UNIFIL troop-contributing countries condemning the targeting of UN personnel. It is at times like these that information becomes important. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the Ministry of Defense, whoever is responsible, needs to state what is what clearly.

Rabi Lamichhane arrested

Just as I was wrapping up this newsletter, news emerged that Rabi Lamichhane, the chief of the fourth-largest party in Parliament, had been arrested in connection with allegations of the misuse of funds from cooperative banking initiatives.

Lamichhane had long been accused of embezzlement and fraud by his political opponents. They had alleged that he was complicit in the illegal transfer of funds from various cooperatives to Gorkha Media, which operated Galaxy 4k Television, where Lamichhane was managing director. A recent parliamentary probe committee found him innocent of the embezzlement but held him responsible for the use of those funds once they came into Gorkha Media. Lamichhane and his party, the Rastriya Swatantra Party, had argued that the committee had given him a ‘clean chit’ but that wasn't so. It was based on the probe committee’s findings that Lamichhane was arrested on Friday evening.

Lamichhane was defiant until his arrest, taking to social media to decry the government’s persecution of him. He alleged that the political party leaders had gotten wealthy off of ill-gotten gains, but he was the one who was arrested. This sentiment will echo with Nepalis all over. The rapacious corruption of the political parties is not news to them; they will see Lamichhane’s arrest as politically motivated. I'm not sure it wasn't. Lamichhane has been hounded by the parties and by the media. He’s not bathed in milk, as the Nepali saying goes, but he is certainly no guilty than the rest of the men who claim to lead this country.

This story is developing and we'll see how it progresses. Lamichhane is a very popular politician and his supporters are not going to take his arrest lying down. There will certainly be protests. But if Lamichhane is truly committed to the law of the land and the systems in place, he will face the music.

That’s all for this week’s round-up. The Deep Dive continues after the break below.

I need your support. KALAM Weekly is a passion project and relies on your goodwill to continue arriving in your inboxes every week. Consider becoming a paid subscriber by clicking the link below:

The deep dive: Reflections on Dashain and death

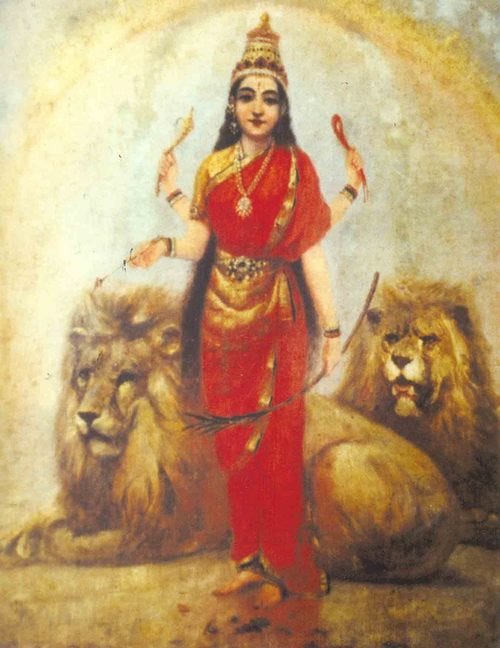

Image: The goddess Durga, in whose name Dashain is celebrated, by Raja Ravi Varma

Dashain has come and Dashain has gone. For a week, we did everything we were once told not to — eat too much, drink too much, gamble away our time. Like Prince Prospero who reveled while the masque of the red death stalked him, we, too, put aside all our woes, our ennui, our deep, permeating sadness, and laughed while the world burned around us. It is what we’ve done every year. And like every Dashain, we waxed nostalgic. We pined for a past seen through rose-colored glasses, when we were younger and things were simpler. We were younger, yes, but things only seemed simpler. The world in all its multifarious glory was all around us but we were only children.

Death permeated this Dashain. Perhaps it had back then too but we were only children. Hundreds of lives lost to floods and landslides just weeks ago. There was no Dashain for their families and there will be no Tihar, just mourning. Traveling around Kathmandu, tika on our foreheads, I couldn’t help but think of those who could not and would not celebrate. But each person’s pain is their own and for those of us untouched by tragedy, life went on. Tika was exchanged, as were envelopes stuffed with dakshina in odd denominations. Heads were showered in jamara and copious amounts of goat meat eaten, alcohol imbibed.

There were no kites in the sky this Dashain, at least none that I could see. There were lingey pings, though. On few and far-between empty plots of land, those rickety makeshift bamboo swings had sprung up. Children reaching for the heavens in wild abandon, held together only by twine. My mother took a swing of her own. “They say you have to leave the ground during Dashain,” she told me cryptically. Who are they? She doesn’t know. What does it mean? That you need to get your feet off the ground. Maybe she made it up, maybe she heard it somewhere, in some other context. But it explained in mystical terms her latent desire to regress to childhood, feel once more a fraction of what it felt like to be a kid. To trust in the simple goodness of strangers to build the swing right, to be oblivious to the simple accidents of fate that end up in broken arms and broken hearts. To once again be only children.

But now that we’re older, our hearts are colder. We know just what is out there. Death, and much worse — madness, forgetting, wasting away, living empty banal lives. Dashain is supposed to be a respite. Time slows down, stops. The drudgery of work is forgotten for but a moment. We live like we’re dying tomorrow. Meeting family and friends, celebrating, eating, drinking, giving away our material wealth. One last hurrah before the final curtain. It isn’t, but we can pretend it is. After all, we are who we pretend to be. Come, bring me life in a cup and I will drink of it, even if the bottom is poisoned.

We now live calculated lives. Our time is fractioned off into meetings and due dates. Our lives bifurcated into the one we live at work and the one we live at home. Our personalities Janus-faced. But for those few days of Dashain, we try to shed our disguises, even though not everyone has the same luxury. Even Dashain is drudgery to those who must work to feed the hordes who arrive like locusts to devour everything placed before them. Someone has to salt and masala the goat, pack it into a haandi, pour in the mustard oil and slow cook it for hours. Someone has to wash those piles of plates and bowls and forks and spoons. Someone has to sweep up all the tika and jamara fallen to the floor like so many best wishes and saubhagyavati bhava.

With the passing of the years, Dashain has become more and more ethereal. Each iteration a simulacrum. Each instance a faded photograph of a time long gone. Each Dashain shrinks and collapses unto itself. The elderly who were just there last year aren’t there anymore. Dashain marks death readily, impressing upon us that next year, there will be even fewer people around. The old die, the young leave, and all that’s left are we in the middle, too young to die, too old to move. And so, we resign ourselves to reminiscing of the days past, living through memory, seeing ourselves as if through a glass darkly.

This Dashain ended with the death of a friend. We were close friends once but had lost touch in recent years, as happens to most of us. Friends too remain in memory, crystallized as they were 10, 15 years ago. I remember her like she was then, all large earrings and crooked smile. I went to her funeral, five days after Dashain tika. I sat in the crowd. I tried not to look anyone else in the eye. I saw her face even though I did not want to. I wanted to remember her full of life, not in a box. I cried. I hugged her sister. It was painful.

At Dashain, death comes home to roost. Death does not stop for Dashain. I’m glad we didn’t know this when we were children. If we did, we might not have flown kites, played langur burja, or whiled our holidays away with nothingness. We would’ve worried, like we do now. We would’ve forgotten to live and we would’ve had no nostalgia, nothing to look back on with a feigned fondness, a wholehearted acceptance of the lie that once, things were better. Once, things were simple. But what did we know? We were only children.

Dashain changes, as do we. Who we were then is not who we are anymore. The Dashain of our childhood is a Dashain in amber. Nothing will bring it back to life. The Dashain of today is something different, a constantly evolving Dashain, morphing and mutating as the young leave the country in search of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness while the old remain, awaiting their inevitable end in the country of their birth. The only constant is passage. Time and the seasons. Death and dolor.

That’s all for this week. I will be back next Friday, in your emails, for the next edition of KALAM Weekly.

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, please consider sharing it with others who might enjoy weekly updates from Nepal or consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading KALAM Weekly! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Your thoughts on Dashain really moved me.

I thoroughly enjoyed your article on Dashain. Very well written. You are spot on reflecting the recent disaster the country has experienced and the feeling of us all during this sad and trouble period of Dashain. It was obviously traumatic for those who suffered yet we went about with the usual fare disregarding the sufferings of those who bore the brunt of the tragedy.